- Home

- Charles Felix

Cleek: the Man of the Forty Faces Page 4

Cleek: the Man of the Forty Faces Read online

Page 4

CHAPTER I

The sound came again--so unmistakably, this time, the sound of afootstep in the soft, squashy ooze on the Heath, there could be noquestion regarding the nature of it. Miss Lorne came to an instantstandstill and clutched her belongings closer to her with a shake and aquiver; and a swift prickle of goose-flesh ran round her shoulders andup and down the backs of her hands. There was good, brave blood in her,it is true; but good, brave blood isn't much to fall back upon if youhappen to be a girl without escort, carrying a hand-bag containingtwenty-odd pounds in money, several bits of valuable jewellery--yourwhole earthly possessions, in fact--and have lost your way on HampsteadHeath at half-past eight o'clock at night, with a spring fog shuttingyou in like a wall and shutting out everything else but a "mackerel"collection of clouds that looked like grey smudges on the greasy-silverof a twilit sky.

She looked round, but she could see nothing and nobody. The Heath was awhite waste that might have been part of the scenery in Lapland for allthere was to tell that it lay within reach of the heart and pulse of thesluggish leviathan London. Over it the vapours of night crowded, analmost palpable wall of thick, wet mist, stirred now and again by someatmospheric movement which could scarcely be called a wind, although, attimes, it drew long, lacey filaments above the level of the denser massof fog and melted away with them into the calm, still upper air.

Miss Lorne hesitated between two very natural impulses--to gather up herskirts and run, or to stand her ground and demand an explanation fromthe person who was undoubtedly following her. She chose the latter.

"Who is there? Why are you following me? What do you want?" she flungout, keeping her voice as steady as the hard, sharp hammering of herheart would permit.

The question was answered at once--rather startlingly, since thefootsteps which caused her alarm, had all the while proceeded frombehind, and slightly to the left of her. Now there came a hurried rushand scramble on the right; there was the sound of a match beingscratched, a blob of light in the grey of the mist, and she saw standingin front of her, a ragged, weedy, red-headed youth, with the blazingmatch in his scooped hands.

He was thin to the point of ghastliness. Hunger was in his pinched face,his high cheekbones, his gouged jaws; staring like a starved wolf,through the unnatural brightness of his pale eyes, from every gauntfeature of him.

"'Ullo!" he said with a strong Cockney accent, as he came up out of thefog, and the flare of the match gave him a full view of her, standingthere with her lips shut hard, and, the hand-bag clutched up close toher with both hands. "You wot called, was it? Wot price me forarnswerin' of you, eh?"

"Yes, it was I that called," she replied, making a brave front of it."But I do not think it was you that I called to. Keep away, please.Don't come any nearer. What do you want?" "Well, I'll take that blessed'and-bag to go on with; and if there aren't no money in it--tumble itout--let's see--lively now! I'll feed for the rest of this week--Gawd,yuss!"

She made no reply, no attempt to obey him, no movement of any sort. Fearhad absolutely stricken every atom of strength from her. She could donothing but look at him with big, frightened eyes, and shake.

"Look 'ere, aren't you a-goin' to do it quiet, or are you a-goin' tomike me tike the blessed thing from you?" he asked.

"I'll do it if you put me to it--my hat! yuss! It aren't my gime--I'mwot you might call a hammer-chewer at it, but when there's summinkinside you, wot tears and tears and tears, any gime's worth tryin' thatpulls out the claws of it."

She did not move even yet. He flung the spent match from him, and made asharp step toward her, and he had just reached out his hand to lay holdof her, when another hand--strong, sinewy, hard-shutting as an ironclamp--reached out from the mist, and laid hold of him; plucking him bythe neckband and intruding a bunch of knuckles and shut fingers betweenthat and his up-slanted chin.

"Now, then, drop that little game at once, you young monkey!" struck inthe sharp staccato of a semi-excited voice. "Interfering with youngladies, eh? Let's have a look at you. Don't be afraid, MissLorne--nobody's going to hurt you."

Then a pocket torch spat out a sudden ray of light; and by it both thehalf-throttled boy and the wholly frightened girl could see the man whohad thus intruded himself upon their notice.

"Oh, it is you--it is you again, Mr. Cleek?" said Ailsa with somethingbetween a laugh and a sigh of relief as she recognized him.

"Yes, it is I. I have been behind you ever since you left the house inBardon Road. It was rash of you to cross the heath at this time and inthis weather. I rather fancied that something of this kind would belikely to happen, and so took the liberty of following you."

"Then it was you I heard behind me?"

"It was I--yes. I shouldn't have intruded myself upon your notice if youhadn't called out. A moment, please. Let's have a look at this younghighwayman, who so freely advertises himself as an amateur."

The light spat full into the gaunt, starved face of the young man andmade it stare forth doubly ghastly. He had made no effort to get awayfrom the very first. Perhaps he understood the uselessness of it, withthat strong hand gripped on his ragged neckband. Perhaps he was, in hisway, something of a fatalist--London breeds so many among such as he:starved things that find every boat chained, every effort thrust backupon them unrewarded. At any rate, from the moment he had heard the girlgive to this man a name which every soul in England had heard at onetime or another during the past two years, he had gone into a sort ofmild collapse, as though realising the utter uselessness of battlingagainst fate, and had given himself up to what was to be.

"Hello," said Cleek, as he looked the youth over. "Yours is a face Idon't remember running foul of before, my young beauty. Where did youcome from?"

"Where I seem like to be goin' now you've got your currant-pickers onme--Hell," answered the boy, with something like a sigh of despair."Leastways, I been in Hell ever since I can remember anyfink, so Ireckon I must have come from there."

"What's your name?"

"Dollops. S'pose I must a had another sometime, but I never heard of it.Wot's that? Yuss--most nineteen. _Wot?_ Oh, go throw summink atyourself! I aren't too young to be 'ungry, am I? And where's a covegoin' to _find_ this 'ere 'honest work' you're a-talkin' of? I'm fairsick of the gime of lookin' for it. Besides, you don't see parties asgoes in for the other thing walkin' round with ribs on 'em likebed-slats, and not even the price of a cup of corfy in their pockets, doyou? No fear! I wouldn't've 'urt the young lydie; but I tell you strite,I'd a took every blessed farthin' she 'ad on her if you 'adn't'vedropped on me like this."

"Got down to the last ditch--down to the point of desperation, eh?"

"Yuss. So would you if you 'ad a fing inside you tearin' and tearin'like I 'ave. Aren't et a bloomin' crumb since the day before yusterdayat four in the mawnin' when a gent in an 'ansom--drunk as a lord, hewas--treated me and a parcel of others to a bun and a cup of corfy at acorfy stall over 'Ighgate way. Stood out agin bein' a crook as long asever I could--as long as ever I'm goin' to, I reckon, now _you've_ gotyour maulers on me. I'll be on the list after this. The cops 'ull knowme; and when you've got the nime--well, wot's the odds? You might aswell 'ave the gime as well, and git over goin' empty. All right, run mein, sir. Any'ow, I'll 'ave a bit to eat and a bed to sleep in to-night,and that's one comfort--"

Cleek had been watching the boy closely, narrowly, with anever-deepening interest; now he loosened the grip of his fingers and lethis hand drop to his side.

"Suppose I don't 'run you in,' as you put it? Suppose I take a chanceand lend you five shillings, will you do some work and pay it back to mein time?" he asked.

The boy looked up at him and laughed in his face.

"Look 'ere, Gov'nor, it's playin' it low down to lark wiv a chap jistbefore you're goin' to 'ang 'im," he said. "You come off your blessedperch."

"Right," said Cleek. "And now you get up on yours and let us see whatyou're made of." Then he put his hand into his trousers pocket; therewas a chink of coins and two half

-crowns lay on his outstretched palm."There you are--off with you now, and if you are any good, turn up sometime to-night at No. 204, Clarges Street, and ask for Captain HoratioBurbage. He'll see that there's work for you. Toddle along now and get ameal and a bed. And mind you keep a close mouth about this."

The boy neither moved nor spoke nor made any sound. For a moment or twohe stood looking from the man to the coins and from the coins back tothe man; then, gradually, the truth of the thing seemed to trickle intohis mind and, as a hungry fox might pounce upon a stray fowl, he grabbedthe money and--bolted.

"Remember the name and remember the street," Cleek called after him.

"You take your bloomin' oath I will!" came back through the enfoldingmist; "Gawd, yuss!"--Just that; and the youth was gone.

"I wonder what you will think of me, Miss Lorne," said Cleek, turning toher; "taking a chance like this; and, above all, with a fellow who wouldhave stripped you of every jewel and every penny you have with you ifthings hadn't happened as they have?"

"And I can very ill afford to lose anything _now_--as I suppose youknow, Mr. Cleek. Things have changed sadly for me since that day Mr.Narkom introduced us at Ascot," she said, with just a shadow ofseriousness in her eyes. "But as to what I think regarding your actiontoward that dreadful boy.... Oh, of course, if there is a chance ofsaving him from a career of crime, I think one owes him that as a duty.In the circumstances, the temptation was very great. It must be ahorrible thing to be so hungry that one is driven to robbery to satisfythe longing for food."

"Yes, very horrible--very, very indeed. I once knew a boy who stood asthat boy stands--at the parting of the ways; when the good that was inhim fought the last great fight with the Devil of Circumstances. If ahand had been stretched forth to help that boy at that time ... Ah,well! it wasn't. The Devil took the reins and the game went _his_ way.If five shillings will put the reins into that boy's hands to-night andsteer him back to the right path, so much the better for him and--forme. I'll know if he's worth the chance I took to-morrow. Now let us talkabout something else. Will you allow me to escort you across the heathand see you safely on your way home? Or would you prefer that I shouldremain in the background as before?"

"How ungrateful you must think me, to suggest such a thing as that," shesaid with a reproachful smile. "Walk with me if you will be so kind. Ihope you know that this is the third time you have rendered me a servicesince I had the pleasure of meeting you. It is very nice of you; and Iam extremely grateful. I wonder you find the time or--well, take thetrouble," rather archly; "a great man like you."

"Shall I take off my hat and say 'thank you, ma'am'; or just thehackneyed 'Praise from Sir Hubert is praise indeed'?" he said with alaugh as he fell into step with her and they faced the mist and thedistance together. "I suppose you are alluding to my success in thefamous Stanhope Case--the newspapers made a great fuss over that, Mr.Narkom tells me. But--please. One big success doesn't make a 'great man'any more than one rosebush makes a garden."

"Are you fishing for a compliment? Or is that really natural modesty? Ihad heard of your exploits and seen your name in the papers, oh, dozensof times before I first had the pleasure of meeting you; and since then... No, I shan't flatter you by saying how many successes I have seenrecorded to your credit in the past two years. Do you know that I have anatural predilection for such things? It may be morbid of me--isit?--but I have the strongest kind of a leaning toward the tales ofGaboriau; and I have always wanted to know a really greatdetective--like Lecocq, or Dupin. And that day at Ascot when Mr. Narkomtold me that he would introduce me to the famous 'Man of the FortyFaces' ... Mr. Cleek, why do they call you 'the Man of the Forty Faces'?You always look the same to me."

"Perhaps I shan't, when we come to the end of the heath and get into thepublic street, where there are lights and people," he said. "That Ialways look the same in your eyes, Miss Lorne, is because I have but oneface for you, and that is my real one. Not many people see it, evenamong the men of The Yard whom I occasionally work with. You do,however; so does Mr. Narkom, occasionally. So did that boy,unfortunately. I had to show it when I came to your assistance, if onlyto assure you that you were in friendly hands and to prevent you takingfright and running off into the mist in a panic and losing yourselfwhere even I might not be able to find you. That is why I told the boyto apply for work to 'Captain Burbage of Clarges Street.' _I_ am CaptainBurbage, Miss Lorne. Nobody knows that but my good friend Mr. Narkomand, now, you."

"I shall respect it, of course," she said. "I hope I need not assure youof that, Mr. Cleek."

"You need assure me of nothing, Miss Lorne," he made reply. "I owe somuch more to you than you are aware, that--Oh, well, it doesn't matter.You asked me a question a moment ago. If you want the answer to it--lookhere."

He stopped short as he spoke; the pocket-torch clicked faintly and fromthe shelter of a curved hand, the glow of it struck upward to his face.It was not the same face for ten seconds at a time. What Sir HoraceWyvern had seen in Mr. Narkom's private office at Scotland Yard on thatnight of nights more than two years ago, Sir Horace Wyvern's niece sawnow.

"Oh!" she said, with a sharp intaking of the breath as she saw thewrithing features knot and twist and blend. "Oh, don't! It is uncanny!It is amazing. It is awful!" And, after a moment, when the light hadbeen shut off and the man beside her was only a shape in the mist: "Ihope I may never see you do it again," she merely more than whispered."It is the most appalling thing. I can't think how you do it--how youcame by the power to do such a thing."

"Perhaps by inheritance," said Cleek, as they walked on again. "Onceupon a time, Miss Lorne, there was a--er--lady of extremely highposition who, at a time when she should have been giving her thoughtsto--well, more serious things, used to play with one of those curiouslittle rubber faces which you can pinch up into all sorts of distortedcountenances--you have seen the things, no doubt. She would sit forhours screaming with laughter over the droll shapes into which shesqueezed the thing. Afterward, when her little son was born, heinherited the trick of that rubber face as a birthright. It may havebeen the same case with me. Let us say it was, and drop the subject,since you have not found the sight a pleasing one. Now tell mesomething, please, that I want to know about you."

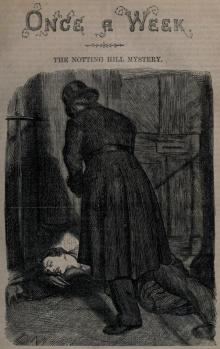

The Notting Hill Mystery

The Notting Hill Mystery Cleek: the Man of the Forty Faces

Cleek: the Man of the Forty Faces